Big Deal Small Business: SDE vs EBITDA vs Cash Flow (Updated)

January 15, 2024 | Issue #96

This is my longest post yet — I thought it was time to refresh & repost this article.

Get a cup of coffee on this holiday Monday. This post provides a foundational overview of understanding SMB profitability.

For all of you launching searches to kick off the new year or in the next few months as your MBA programs end (or even those of you knee deep in a search) — please read this post if nothing else I write.

Email me if any of it doesn’t make sense.

If you come from an private equity / M&A background, this post should quickly bridge you from PE-style EBITDA to SMB-style EBITDA — you will be able to skim through it fast.

I’ve seen so many searchers not understand these fundamentals and then waste so much time looking at deals that were dead from the jump.

Or worse yet, they CLOSE deals that should’ve been killed on day two. Simply because they don’t understand the difference between Seller Discretionary Earnings, EBITDA, and Cash Flow.

But after reading this, that won’t be you (hopefully). Let’s dive in.

Definitions

You need to know how to think about profitability & multiples in a consistent manner, or you risk misunderstanding what you're buying.

The rest of this article explains the profitability concepts as I utilize them practically — there are lots of ways to utilize them, this is just my practice. Feel free to adjust them to what makes sense to you, but the point is you need to be consistent across deals to make sure you’re comparing them correctly.

First, these are the literal abbreviations:

EBITDA = Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation & Amortization

SDE = Seller Discretionary Earnings

FCF = Free Cash Flow (honestly, I don’t use this — I use the two below)

LFCF = Levered Free Cash Flow (FCF after debt payments)

UFCF = Unlevered Free Cash Flow (FCF before debt payments)

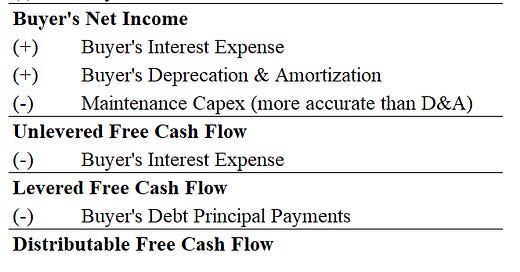

At the end of this post, I have a clear accounting statement-style walk through from Net Income all the way through each of the key concepts.

EBITDA

In SMB acquisitions, we have to distinguish between Seller’s EBITDA — how much EBITDA the Seller has been earning historically — versus Buyer’s EBITDA — how much EBITDA you, the buyer, will generate.

Let’s start with Seller’s EBITDA — later on, I’ll show you how to bridge to Buyer’s EBITDA.

Purpose of EBITDA: To compare businesses' operating performance on apples-to-apples basis by stripping out anything related to 1) capital structure or 2) capital intensity.

Capital Structure means how much debt and equity the business has. A business with a lot of debt will have lower Net Income (because it more interest expense) than a business with lower debt, even if the two core biz operations are otherwise the same.

Why do we not care about Capital Structure? Because as a buyer, we're going to reset the whole capital structure anyway. Your profitability and cash flow depend on your acquisition capital structure, not the existing capital structure. When we get to cash flow, we will subtract these costs based on our capital structure. But for now, we want to strip out all Capital Structure impacts to get to a clean number that is consistent for buyer and seller.

As a result, we add back Interest Expense, as that is a function of capital structure.

Capital Intensity focuses on how much capital a business needs to invest in an ongoing way (acquire equipment, invest in R&D/IP, etc.) to consistently generate its earnings. Depreciation of hard assets or amortization of intangible assets represents a cost related to capital intensity, so we add that back.

Why do we not care about Capital Intensity? We do care about it! The problem is Depreciation & Amortization are accounting concepts, not cash concepts, which can lead to them muddying the waters when comparing two businesses' core operating performance.

For example, let's say that 12 years ago, Business A bought $100K of heavy equipment with 20 years of life. Accounting/tax rules may allow that equipment to be depreciated to zero over 10 years, so $10K/year. Today, 12 years after buying the equipment, Business A has no depreciation costs on P&L even though they can keep using the equipment for 8 more years.

On the other hand, say Business B bought $100K of heavy equipment only 7 years ago, so they still depreciate at $10K/year for 3 more years.

They both have the same capital intensity (need to spend $100K every 20 years on heavy equipment to generate their operating profit), but a function of time/accounting rules makes Business A's Net Income higher than Business B's Net Income.

As a result, in EBITDA, we add back Depreciation & Amortization Expense to normalize for the weirdness of timing & accounting rules. (Check the bonus section below though for a way to incorporate Capital Intensity back in a more fair way).

Lastly, a company's income tax burden is largely related to its capital intensity and capital structure as depreciation, amortization, and interest expense are all tax-deductible expenses. It can also vary based on each company's corporate structure, ownership profile, etc. Again, we care about our taxes going forward (under our acquisition structure), not looking backward. So, we add back income tax as well to make everything apples-to-apples.

(Note - we generally don’t add back other taxes, such as city licenses — those are just ongoing operating expenses, unrelated to profits, capital structure, capital intensity, etc.)

Hopefully it is clear that EBITDA is nowhere close to Cash Flow. But it serves its purpose as a profitability metric of unlevered (read: no debt) operating performance regardless of age of assets, ownership structure, etc.

Important: Everything above got us to “Seller’s EBITDA” — this is an small business buying concept — I will walk you down to Buyer’s EBITDA in a couple steps below. Keep going.

Bonus Note #1: PE firms commonly use EBITDA minus Maintenance Capex to incorporate Capital Intensity without the confounding variable of time or accelerated depreciation. Maintenance Capex is basically how much in Capital Expenditures do you need to spend on an annualized basis to maintain current profitability. (Distinct from capex required to generate growth).

In the case of Business A and B above, you could say they both need to spend $5K/year in maintenance capex if they need to buy $100K of equipment every 20 years — even though neither business literally spend $5K in cash per year. So you could add back their depreciation to get to EBITDA, then subtract $5K in Maintenance Capex.

Bonus Note #2: It is common for Sellers to include a number of "adjustments" or "addbacks" to EBITDA that represent unusual or one-time events. I've written a post exploring that concept, so check that out if you're curious.

Seller Discretionary Earnings

“SDE” is a concept that only exists in small business buying. It doesn't exist in most big business buying (i.e. middle market private equity, my former profession).

Why? Because most big businesses have distinct ownership & management teams. They are not the same person.

In PE, when we bought a business, the owner tossed us the keys and that was it. There was no change to payroll as the owners were usually financial owners, with no operating role or salary (or personal expenses running through the business).

SMB are different, with the owner usually playing a primary role in management, often uses the business as a personal piggy bank, and takes a salary. As a result, we use SDE as a way to compare SMBs.

For example, imagine two businesses in the same industry with $1M in revenue and $200K in Seller’s EBITDA. Both have active owners. One of the owners takes a $200K salary, the other takes a $100K salary. Given they are owners, they are picking their salaries arbitrarily here.

So which business is more profitable then? If you used EBITDA, they look the same. But in reality, one is generating $400K in SDE and the other is generating $300K in SDE (EBITDA + Owner Salary). The day you take over the business and the Seller walks away, that’s the cash flow you have to play with.

To be clear — it is not the cash flow YOU will actually generate for yourself — that’ll be covered further below. But it’s the most accurate starting point to figure out what YOUR cash flow will be.

Bonus Note #1: It is common to addback owner’s personal expenses (if you can verify them) from EBITDA to SDE. Standard ones include owner’s medical insurance (though you’ll have to deduct your own later, assuming you’ll need insurance), unrelated expenses such as kids’ school tuition, country club dues, etc.

In summary, the purpose of SDE is to provide a starting point to compare SMBs’ profitability regardless of how the owner chooses to take out their profits. You generally do not compare SDE itself — it allows you to get to Buyer’s EBITDA and other metrics that compare across deals.

Buyer's EBITDA

You thought I was going to cash flow next. Nope! I called it Seller's EBITDA up there for a reason. Now we move to Buyer's EBITDA — this is what we care about as buyers.

This is a CRUCIAL step in SMB buying (that largely doesn't exist in private equity / larger M&A).

Put simply, there will be significant new costs required to run this business as you replace the Seller. The two biggest are 1) replacing the functional roles the seller plays and 2) your own salary to run the business.

Think of Buyer's EBITDA as "Investor's EBITDA" -- what EBITDA are the investors buying. Even if you don't have investors, separate out the value of your time in the business when thinking about the investment returns of the deal. If you have no investors, you’re playing two roles — investor & CEO (though in a small business, you’re actually a glorified general manager).

For example, let's say the Seller is currently the GM and salesperson. You may be able to take over the GM role, but you'll have to hire a salesperson at $65K/year.

In that scenario, I would take SDE, lower it by your salary as GM (say $100K) and the salesperson salary of $65K/year. That's Buyer's EBITDA.

The list here can be long! Sure, you can take over the seller’s GM responsibilities, but was she also changing the oil on the big diesel trucks you now own? If so, unless you’re planning to take on that role, you need to budget in cost for an auto shop to handle that for you.

Other examples include things like built-in rent raises...an SBA deal usually requires the landlord agreeing to a new 10-year lease extension. If they only agree to that in exchange for a $10K rent increase, you need to deduct that from SDE to get to Buyer's EBITDA as well.

When you go through your insurance due diligence (I recommend Oberle Risk) and it reveals you need an extra $5K/year in premium due to missing coverage, you need to account for that in Buyer’s EBITDA.

When all is said & done, your Buyer’s EBITDA is effectively what the NEXT buyer of the business will see.

Cash Flow

Finally, cash flow. There are a TON of ways to define cash flow, but I categorize cash flow into three buckets:

Unlevered Free Cash Flow = cash flow generated by your business setting aside your debt; importantly, this has to account for capital expenditures (reinvestment into the business) that is required to keep the business steady, aka Maintenance Capex.

Levered Free Cash Flow = cash flow generated by your business including the cost of your debt

Distributable Free Cash Flow = cash flow available to the owner to take as a dividend or reinvest in the business

Let’s walk through all the steps first, and then some explanation:

Okay, there’s a lot there, including a few steps I through at you without explanation.

Here’s the intuition — I explained how to get to Buyer’s EBITDA, which by definition ignores Interest, Taxes, and Depreciation & Amortization (“D&A”).

Unfortunately, those are represent real cash costs, so we need to account for them to understand Cash Flow.

First — taxes. From EBITDA, we deduct Interest and D&A as those are tax-deductible expenses. That gets us to Taxable Income — then you apply YOUR effective tax rate (not the company’s historical tax rate) based on your entity structure, your investor base, etc.

Simple tax assumptions:

If you’re going to be a C-Corp, assume 28%.

If you’re going to be an LLC with pass-through taxes, assume 40%.

This deserves a post of its own, but just giving you rough numbers so you can move through the exercise. This is not tax advice, get a CPA or tax lawyer to help you with that.

Second — D&A. This is an accounting concept that measures how much our long-term assets decline in value, which in theory gives us an idea of when we need to replace them to keep the business afloat.

Unfortunately, as explained earlier in this post, accounting rules for D&A don’t really reflect real life. Instead, you need to figure out Maintenance Capex on your own. This is the average annual amount of reinvestment required for the business to stay running as-is.

For example, if you have $100K of equipment that has a 10-year useful life, you have $10K/year in Maintenance Capex, even though you actually only spend $100K every 10 years. Think of it as funding a reserve — each year, you should set aside $10K of cash into that reserve so that when you have to shell out the $100K, you are good to go.

Given the difference between D&A and Maintenance Capex, we add back D&A (given we deducted as a tax-deductible expense, then subtract Maintenance Capex instead.

Then we add back Buyer’s Interest Expense. Why? Because I want to understand our Unlevered Free Cash Flow first, which is before the impact of debt. Think of it like this — if you didn’t grow the business but just slowly paid off the debt, this how much cash you would generate once the debt was gone.

(Yes, I’m ignoring the interest tax shield impact, simplifying assumption.)

Then we subtract that Buyer’s Interest Expense to get to Levered Free Cash Flow. This accounts for the cost of debt i.e. the interest rate, but not the total debt payment.

And then we subtract the actual debt principal payments to get to Distributable Free Cash Flow.

By the time we get to Distributable Free Cash Flow, we have 1) paid all operating costs, 2) reinvested in our capital equipment, 3) paid our cost of debt, 4) paid our debt principal, and 5) paid our income taxes.

This is now the cash you have left over to either 1) take out of the business, or 2) reinvest for growth.

Bonus Note #1: I ignored working capital above — that deserves a standalone post. But in a steady-state business (i.e. one that is not growing or shrinking), working capital should roughly stay the same, so it does not have an impact on cash. But if you are modeling that the business will grow going forward, you will have a drag on cash as working capital increases with size (for most businesses).

Using These Metrics To Assess a Deal

How do these numbers actually help you understand the quality of a deal or the valuation of the business?

The two key concepts are 1) comparability and 2) return profile.

By applying this financial diligence process to all businesses you look at, you’ll be able to compare their financials on an apples-to-apples basis.

In a small business context, my favorite metrics are Unlevered Free Cash Flow Yield (“UFCF Yield”) and Levered Free Cash Flow Yield (“LFCF Yield”).

First, UFCF Yield. This is simply unlevered free cash flow divided by total purchase price (including transaction fees).

So if you're buying a business for $5 million with $250K in fees, your purchase price is $5.25 million. If your expected unlevered free cash flow is $700K, your yield is 13% ($700K/$5.25M).

In other words, setting aside any growth or the impact of leverage (debt), the deal should return 13% / year just for holding the business steady.

Second, Levered Free Cash Flow Yield. This is levered free cash flow divided by total equity invested into the deal (not total purchase price), as the point of leverage is to reduce your equity requirement.

In the above example, let's assume the $5.25 million price is funded using $1M in equity and $4.25M in debt. Let's say that debt carries $400K in interest expense, so your levered free cash flow is $300K. That means your levered free cash flow yield is 30% ($300K/$1M).

So if you never pay down your debt and just hold the business steady, you should generate a 30% annualized return on equity.

Now compare two deals with the same unlevered profile:

Deal 1: $5.25 million (incl. $250K fees) to buy $700K of UFCF. But banks love the business model, so are willing to lend you $4.25 million in debt with $400K of interest per year.

Deal 2: Also $700K of UFCF, but the banks are sketched out by the business, so are only willing to fund $2M of debt at $200K of interest per year, leaving you $500K of LFCF.

Both companies have the same UFCF, but one of them has a lower cost of capital as banks view it as safer.

Deal 1 has a 30% LFCF Yield and 13% UFCF Yield, as explained above.

In order for Deal 2 to also generate a 30% LFCF Yield with $500K of LFCF, you can only fund up to $1.67 million of equity. Combined with the $2M of debt, that is a max purchase price (incl. say $170K of fees) of $3.67 million for Deal 2.

So you can only pay $3.67M if you want to generate the same return on equity. But this does boost up your UFCF to 19%, due to the lower price — the deal itself is effectively cheaper on an unlevered basis.

Now let’s convert that to EBITDA multiples, the most common valuation metric.

Let’s say both companies generate $900K of Buyer’s EBITDA.

Deal 1 is $5M purchase price before fees / $900K EBITDA = 5.6x multiple

Deal 2 is $3.5M purchase price before fees / $900K EBITDA = 3.9x multiple

Do you see the issue here? Deal 1 looks super expensive relative to Deal 2, but they are actually the exact same LFCF Yield on Equity.

This is why EBITDA multiples are usually only comparable within one industry, where most businesses have a similar cost of capital.

Take it one step further to SDE multiples, which SMB brokers choose to focus on:

Let’s say Deal 1 has $600K in replacement costs

Let’s say Deal 2 has only $100K in replacement costs

Given they’re both the same Buyer’s EBITDA (which subtracted replacement costs), these are their SDEs:

Deal 1 = $900K + $600K = $1.5 million SDE

Deal 2 = $900K + $100K = $1.0 million SDE

And therefore SDE multiples:

Deal 1: $5M price / $1.5M SDE = 3.3x SDE multiple

Deal 2: $3.5M price / $1.0M SDE = 3.5x SDE multiple

We’ve now flipped from the EBITDA multiple discussion — now Deal 2 looks “expensive” relative to Deal 1.

But again — both have literally the exact same Levered Free Cash Flow Yield on Equity.

The discussion on valuation can be endless from here — this post is meant to give you some tools & language to begin your exploration. I’ll plan to write more on the concept in the future.

Conclusion

That was…a lot. Props to you if you read through the end. I hope that all made sense and was reasonably helpful.

For thoughts or feedback, you can always reply to this email or post/DM me on Twitter. And quick reminder — if you need deal team recommendations for your deal, here’s my Trusted Deal Team list.

Thanks,

Guesswork Investing

Fantastic as always. Thanks for writing. I still use the spreadsheet version of this (from "Gut Reaction Deal Math"), which you posted last year I think. Would love to participate in buyer/ETA communities that you facilitate. Cheers.

Love your Substack. I'm at a growth equity fund, personally looking into ETA. Do you have Excel model templates to share with the community / plan to post about ETA financial modeling?